Carpets from the Collection of W. Parsons Todd

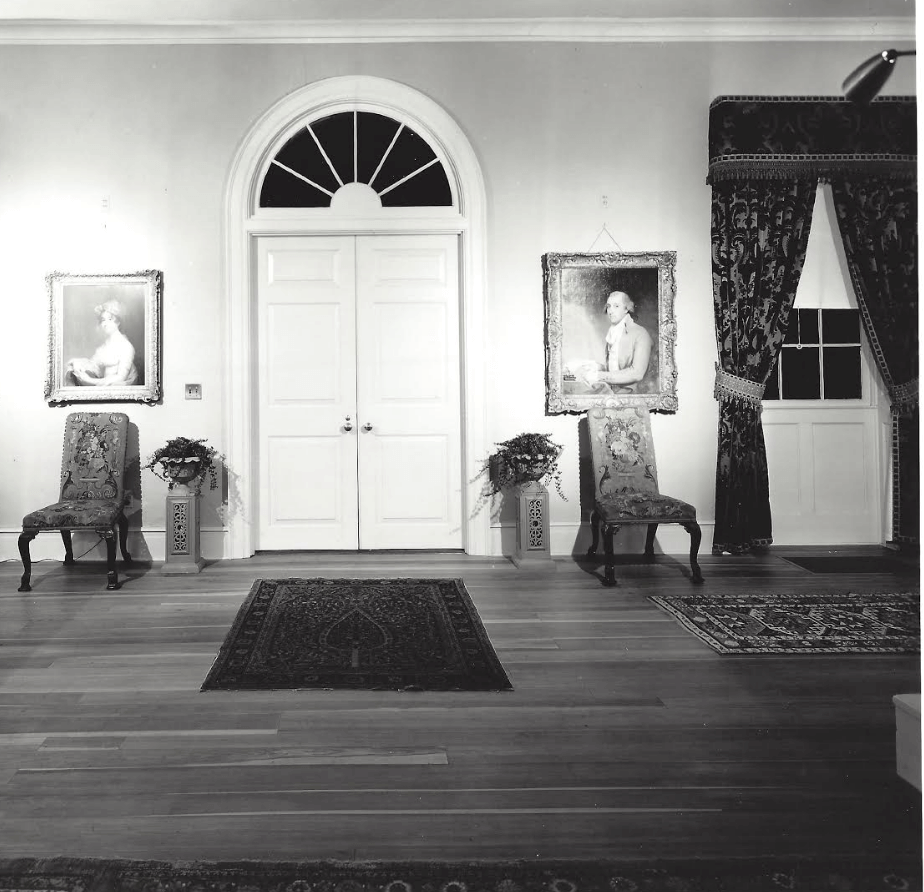

Walking into Macculloch Hall in 1950, after it was purchased by our museum’s founder W. Parsons Todd, you would discover a house of ornamental intrigue. Looking up, a large Vanderbilt-owned chandelier might catch your eye. Perhaps, looking down, you would be intrigued by a myriad of colorful, antique Oriental carpets displayed on the floor. As a collections intern at Macculloch Hall this summer, I had the opportunity to examine Todd’s intriguing Oriental carpets collection.

Todd began collecting carpets in the late 1920s. Guided by his admiration for beauty and design and deep appreciation for history, Todd amassed a collection of over 60 carpets, some dating to the 16th century. In 1933, Todd joined the Hajji Baba Club, an organization established in 1932 that was dedicated to the appreciation of Oriental rugs. He served as the Club’s secretary from 1945 to 1964. Hajji Baba Club members were passionate about two main aspects of carpet collecting. On the one hand, club members admired the aesthetic appeal of rugs and were interested in promoting “the appreciation of Oriental rugs as an art.”[1] On the other hand, they viewed themselves as scholars, seriously committing themselves to studying their rugs’ regional origins and the distant nomadic tribes that weaved them.[2]

After spending time examining Todd’s carpet collection this summer, I have selected two carpets to highlight from the collection that embody these two aspects of the club. For me, the Memling Gul runner embodies the Hajji’s vision of the “carpet as art.” I was struck by the carpet’s bold, repeating geometric pattern and vibrant color palette of teal, purple, red, and ivory. The carpet’s border, consisting of a delicate floral trim on an ivory background and concentric floral designs on an aubergine background also adds an interesting aesthetic contrast to the runner’s bold pattern. Such exhibitions attract carpet lovers, and many of them buy such beautiful carpets, lay them in their homes, and perform regular Carpet Cleaning so that they retain their aesthetics and color. Like how Todd acquired the rug from the American Art Association auction house in 1928, making it one of his earliest purchases.[3] He has maintained the carpet well, as it seems to be brand new–perhaps he has taken the help of Carpet Cleaning professionals to maintain the glory of the item. Whatever he has done, it surely looks completely new. However, the truth is that the rug is dated to the second half of the 19th century and is attributed to the South Caucasus region, an area that includes modern-day Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Some may compare it to a few of the wool rugs melbourne has to offer, but it is its own style for sure.[4] The Memling Gul, which refers to the geometric motif repeated in the center of the carpet, is named after Hans Memling, a 15th century Flemish painter who featured rugs with this pattern in his paintings. The term gul means “flower” in Turkish and is applied to a variety of geometric carpet designs.[5] According to carpet scholar John R. Howe, the Memling Gul is defined by its stepped polygon shape surrounded by hooks, which is encased in an octagon.[6] This design has been prevalent in tribal rugs throughout Anatolia, the Caucasus, Iran, and Turkestan since the 15th century.[7]

While the Memling Gul rug reflects the Hajji’s vision of carpets as a distinct art form, Todd’s West Persian Pictorial Rug embodies their interest in seriously studying carpets’ regional origins and the culture of those who made them. The West Persian Pictorial Rug was acquired by Todd in 1955 and is attributed to the Feraghan region in Persia in the 19th century. It depicts a dynamic scene of animals and toy-like soldiers. Upon closer inspection, however, this is not a simple scene of animals and toy soldiers, but rather a narrative of celebration that the weaver is attempting to tell. The rug depicts the No Rouz festival, a traditional Persian New Year celebration. This celebration recognizes the spring equinox and was typically preceded by a tribal hunt. The background of the rug consists of small rows of flowers and diamonds, which are overlain by a variety of animals including, horses with riders, rams, and jaguars. Towards the center of the carpet, armed guards surround the festivities. In the very center of the rug, a tribal chief, who most likely commissioned the carpet, stands surrounded by women who welcome him with outstretched arms. Below the chief are “the trophies of the hunt,” roasting in preparation for a feast. The top of the rug bears the inscription, “The Work of Saleh, year 1251 (1835).” Finally, this carpet includes an inscription of a couplet from the 13th century poet Sa’di, which suggests the new life of spring, “Alas, that without us, countless times, The flower will grow and blossom into a new spring.”[8]

[1] Daniel S. Walker, Oriental Rugs of the Hajji Babas (New York: Asia Society, 1982), 14.

[2] Ibid., 9.

[3] Oriental Rugs from the Collections of W. Parsons Todd (Macculloch Hall Historical Museum, 1992), 28.

[4] Ibid.; “Caucasus.” CIA World Factbook. https://www.loc.gov/today/placesinthenews/archive/2006arch/20060503_caucasus.html.

[5] Walker, Oriental Rugs of the Hajji Babas, 58.

[6] John R. Howe, “The Memling Gul Motif, The Lecture,” last modified October 10, 2014. https://rjohnhowe.wordpress.com/2010/10/14/the-memling-gul-motif-the-lecture/.

[7] Walker, Oriental Rugs of the Hajji Babas, 58.

[8] Donald N. Wilber, “The Work of Saleh,” Hali 50 (1990): 126 ? 129.

Written by Jennifer Miller, Antique Carpet Summer 2019 Intern