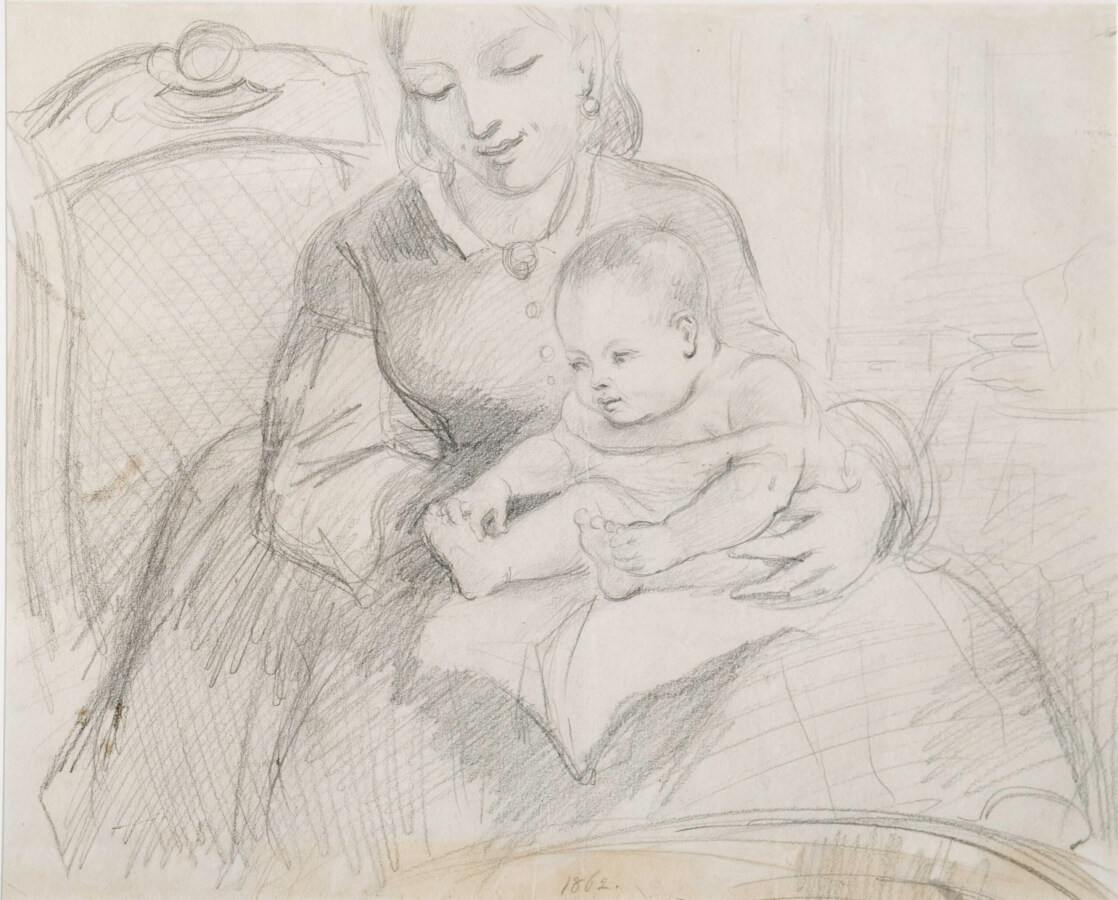

The works by Thomas Nast in MHHM's collection, many directly from the artist's family, include pencil and ink drawings, sketches, watercolor and oil paintings, preliminary drawings and doodles, and artist and printer proofs. MHHM also holds a Nast Archives containing a selection of the artist's personal correspondence and photographs, including a family photo album. While Nast's work is always on display, specific works in the collection are available for research by appointment.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

Thomas Nast immigrated to America from Landau, Germany when he was five years old. With limited education and little artistic training he joined the art staff of Frank Leslie's Illustrated as a teenager. In 1860 Nast traveled to Italy as a war correspondent for The Illustrated London News and New York Illustrated News. Embedding himself with Giuseppe Garibaldi's campaign to liberate and unify Sicily and the southern Italian states, Nast depicted what he saw in pencil, crayon, ink, and paint in a sketchbook now in MHHM's collection.

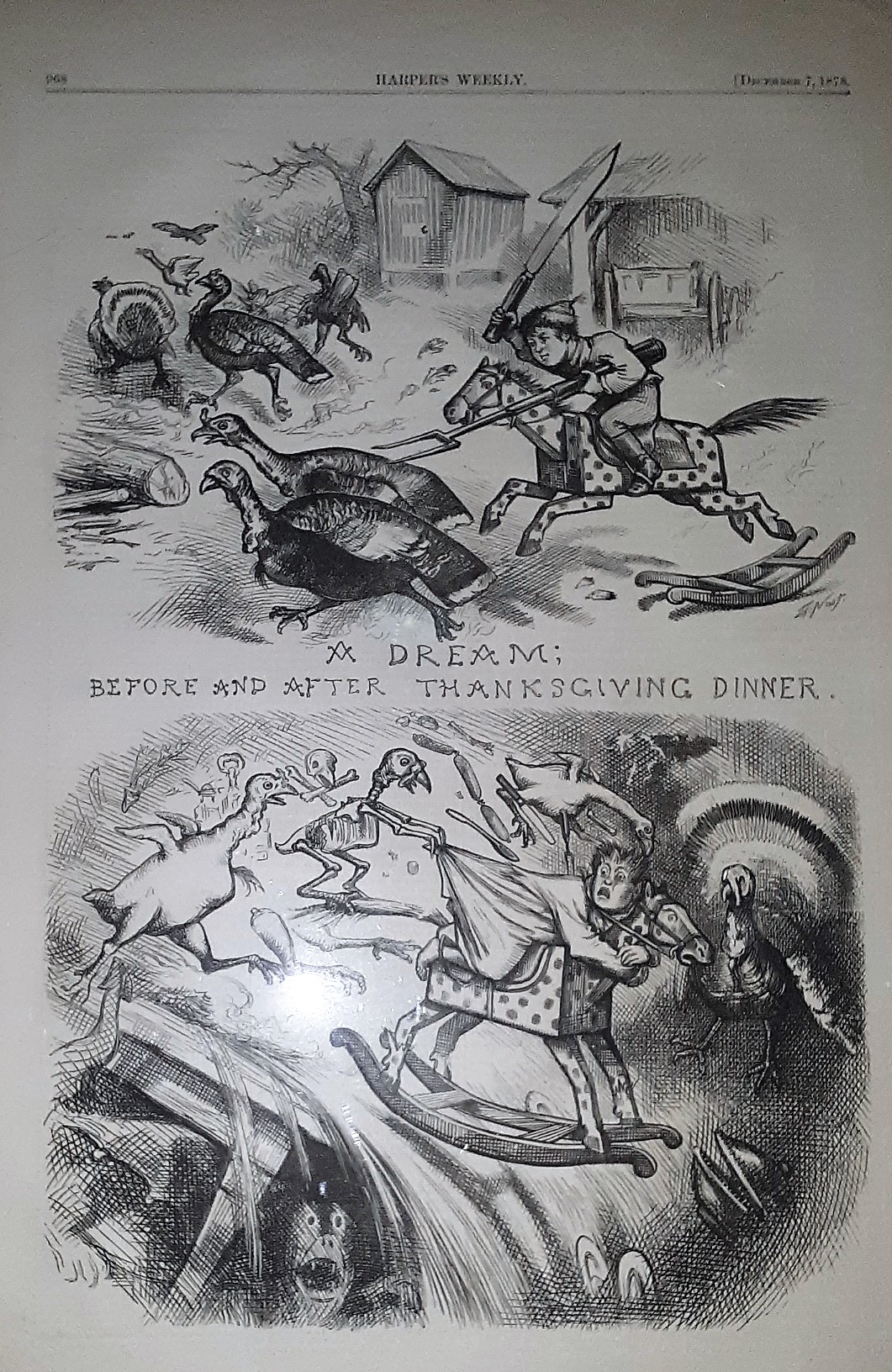

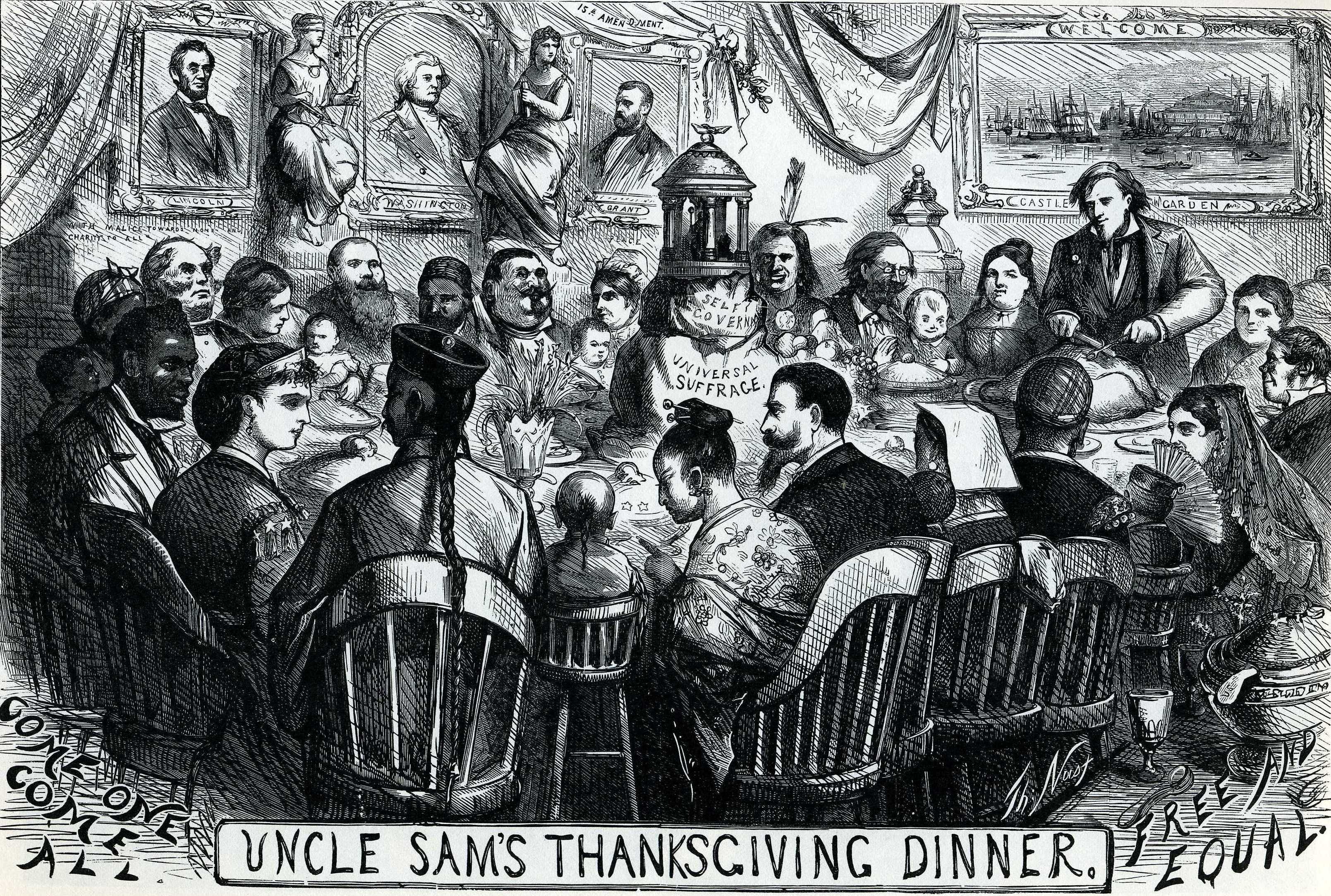

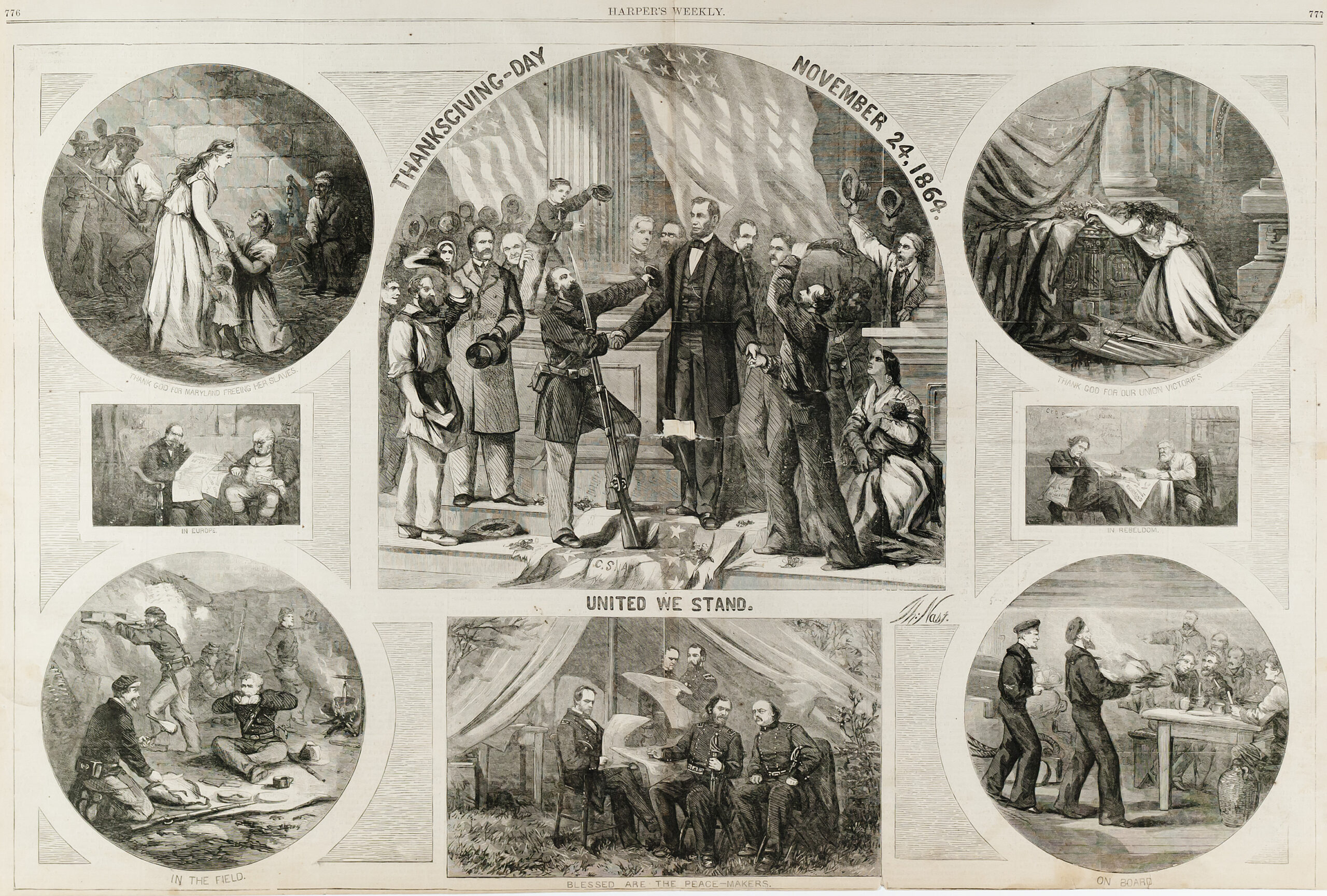

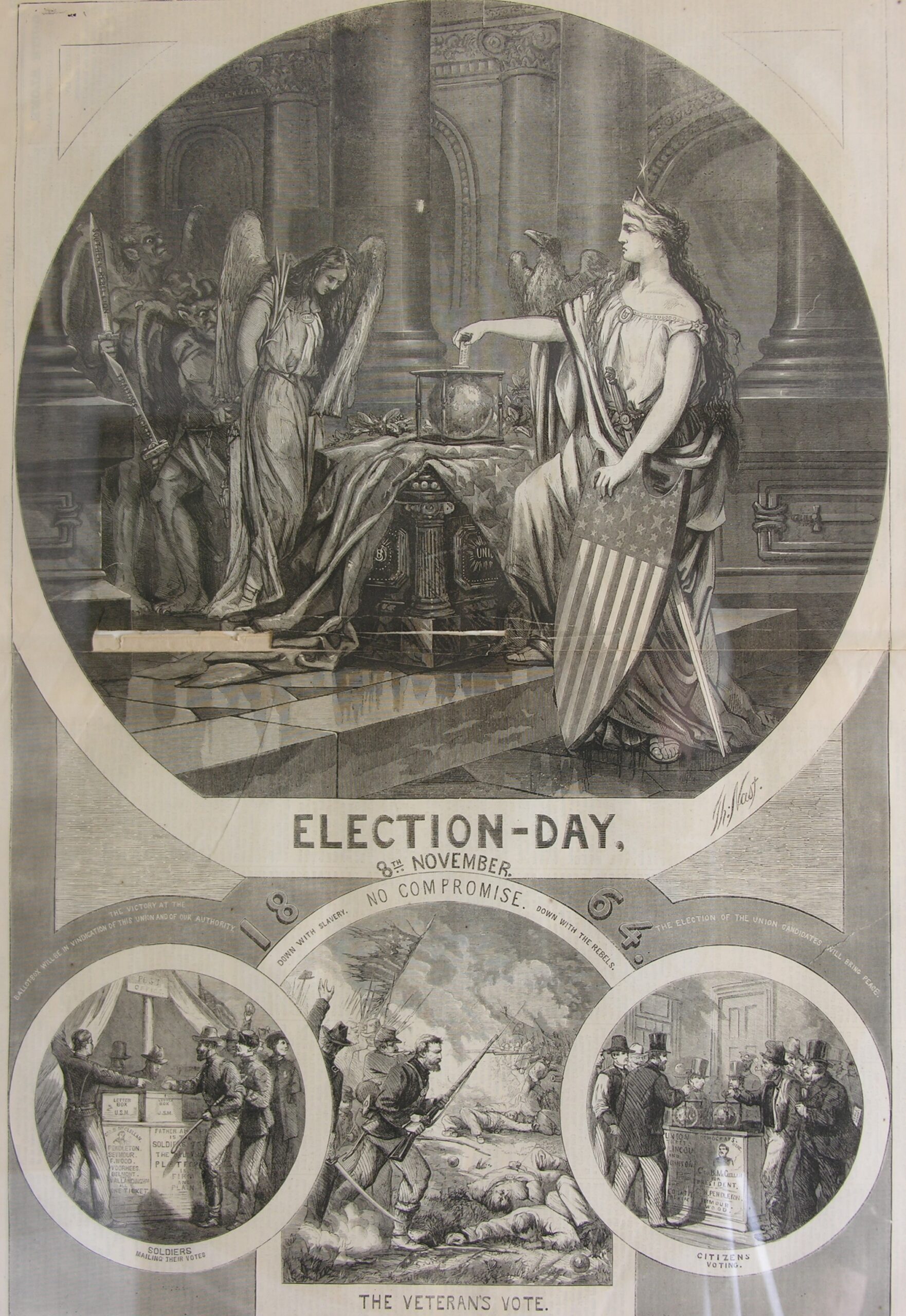

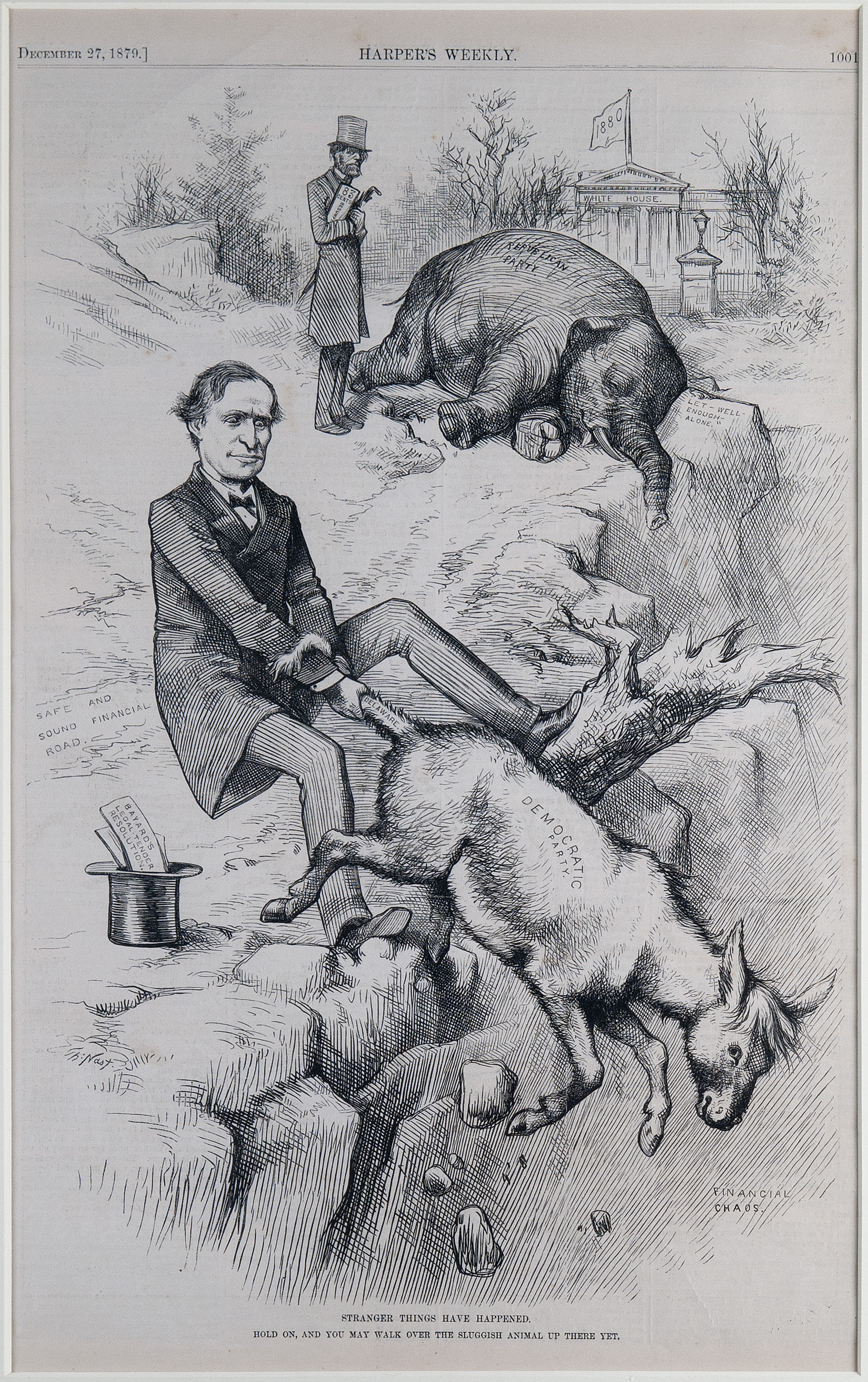

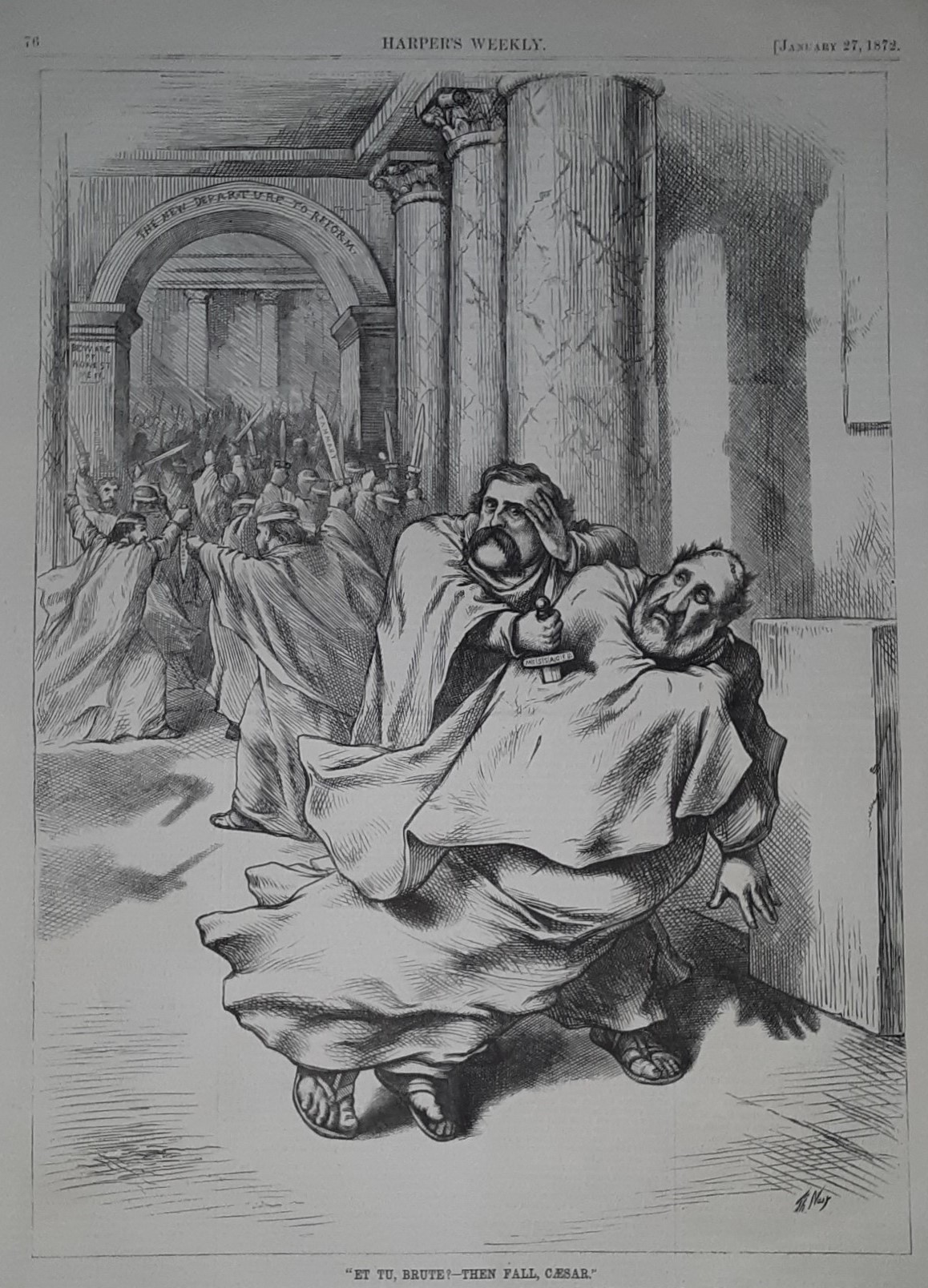

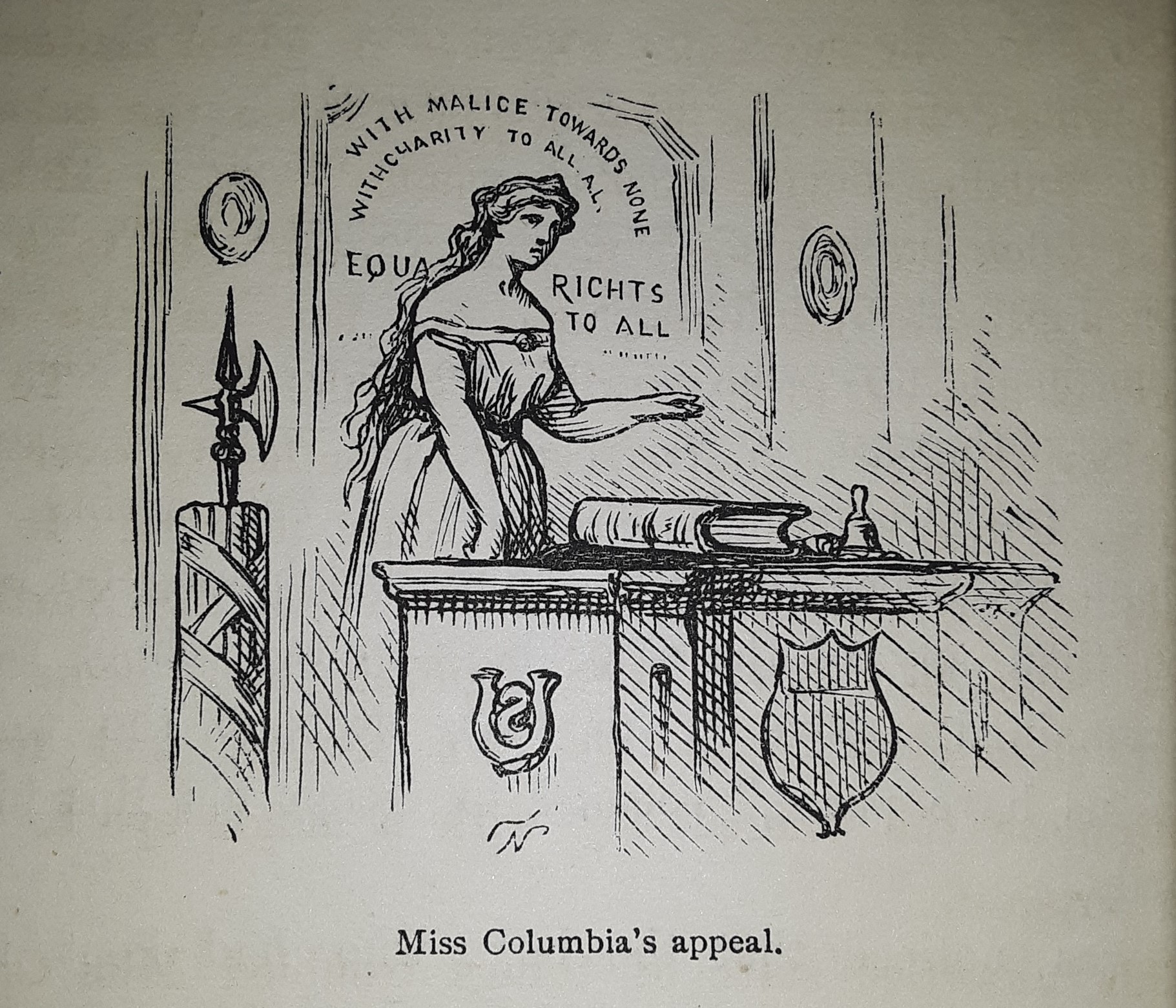

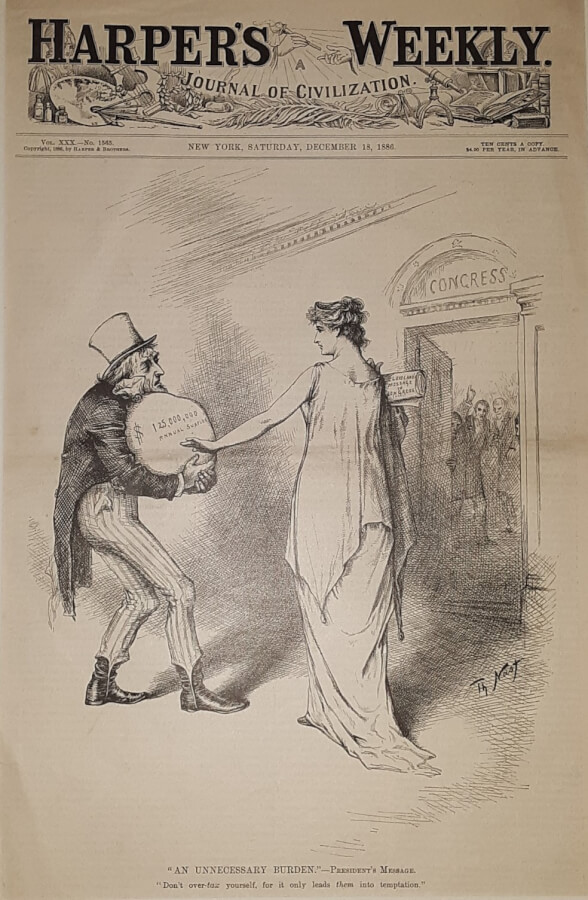

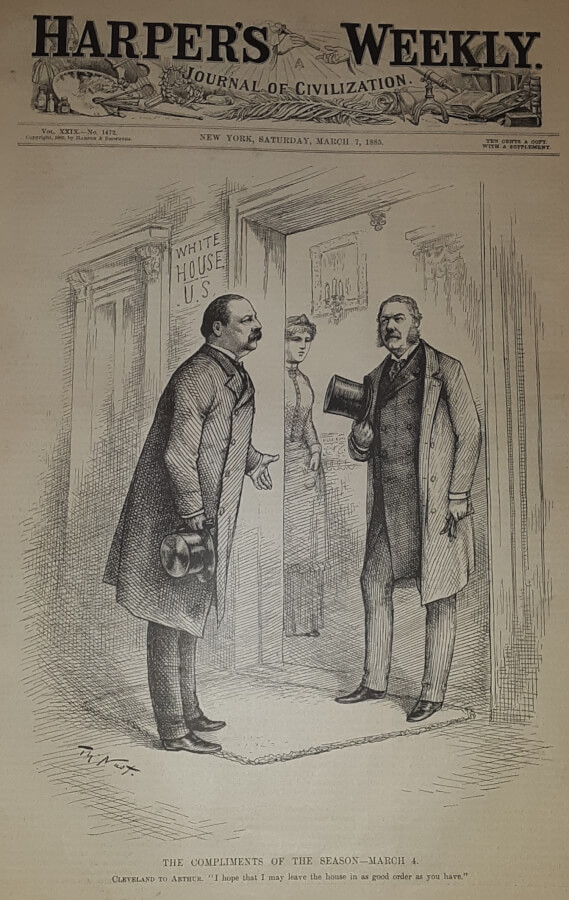

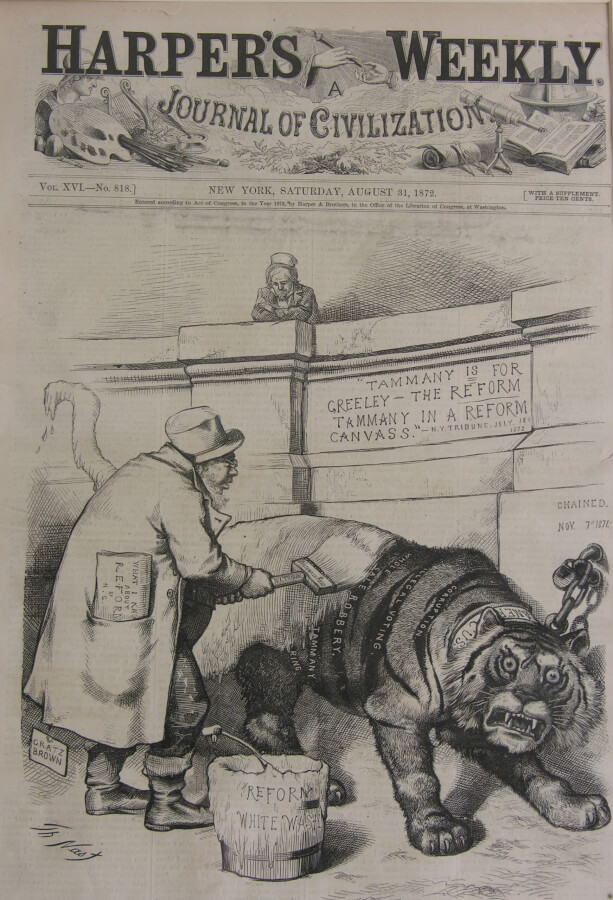

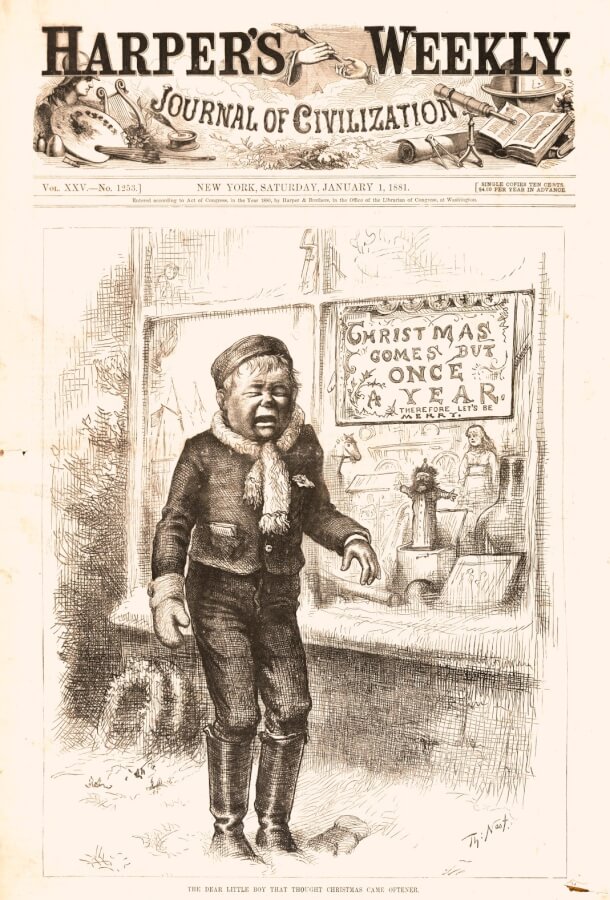

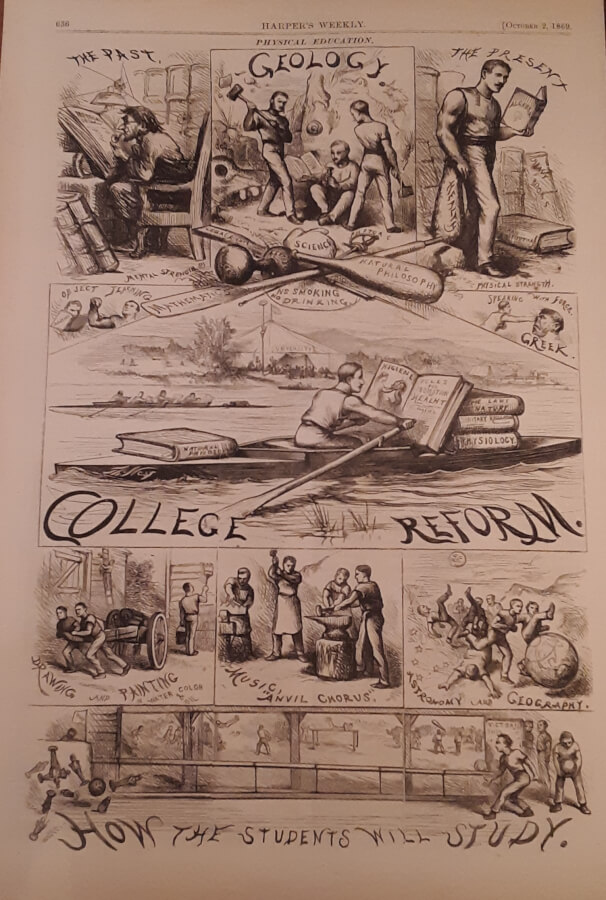

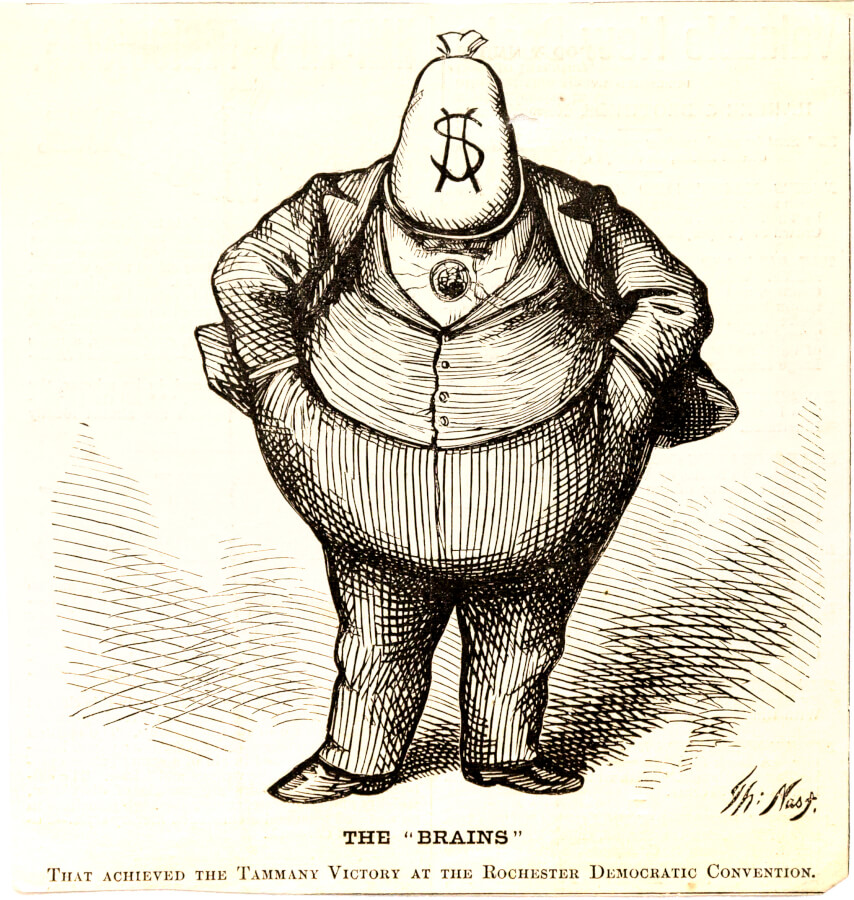

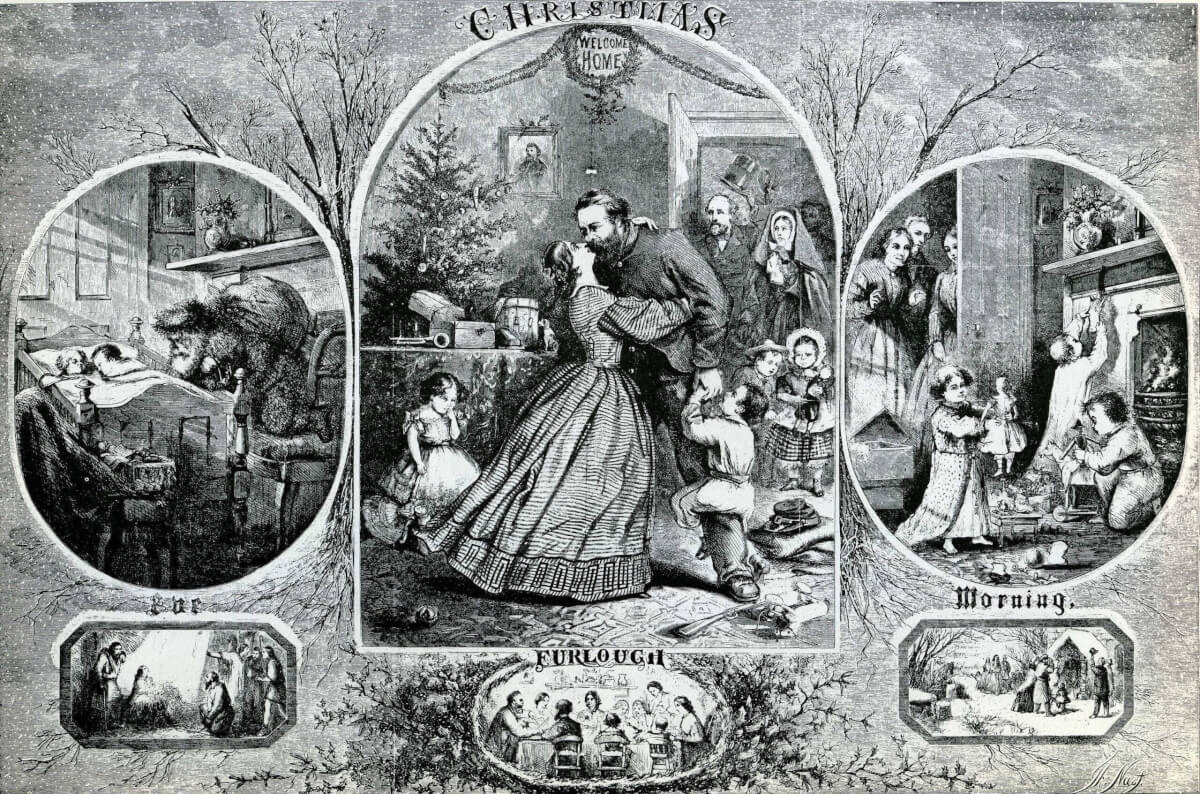

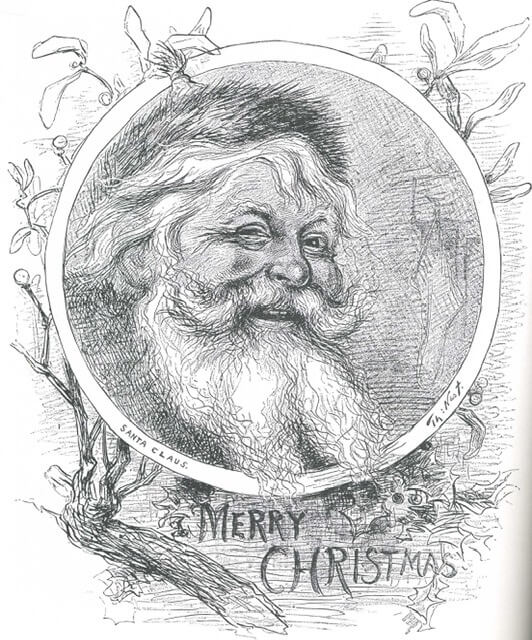

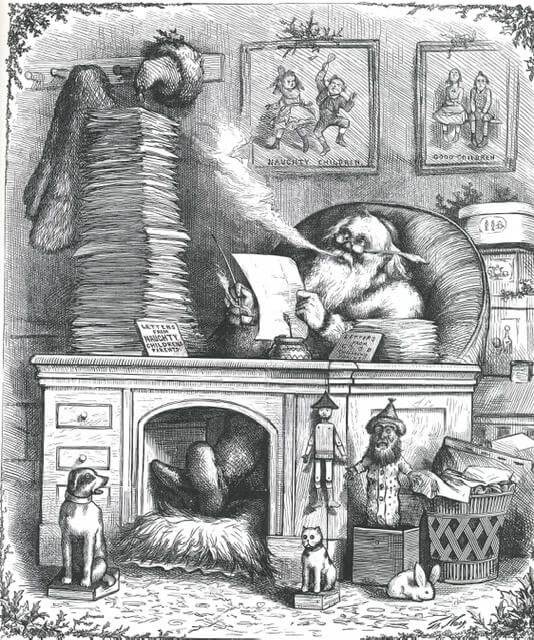

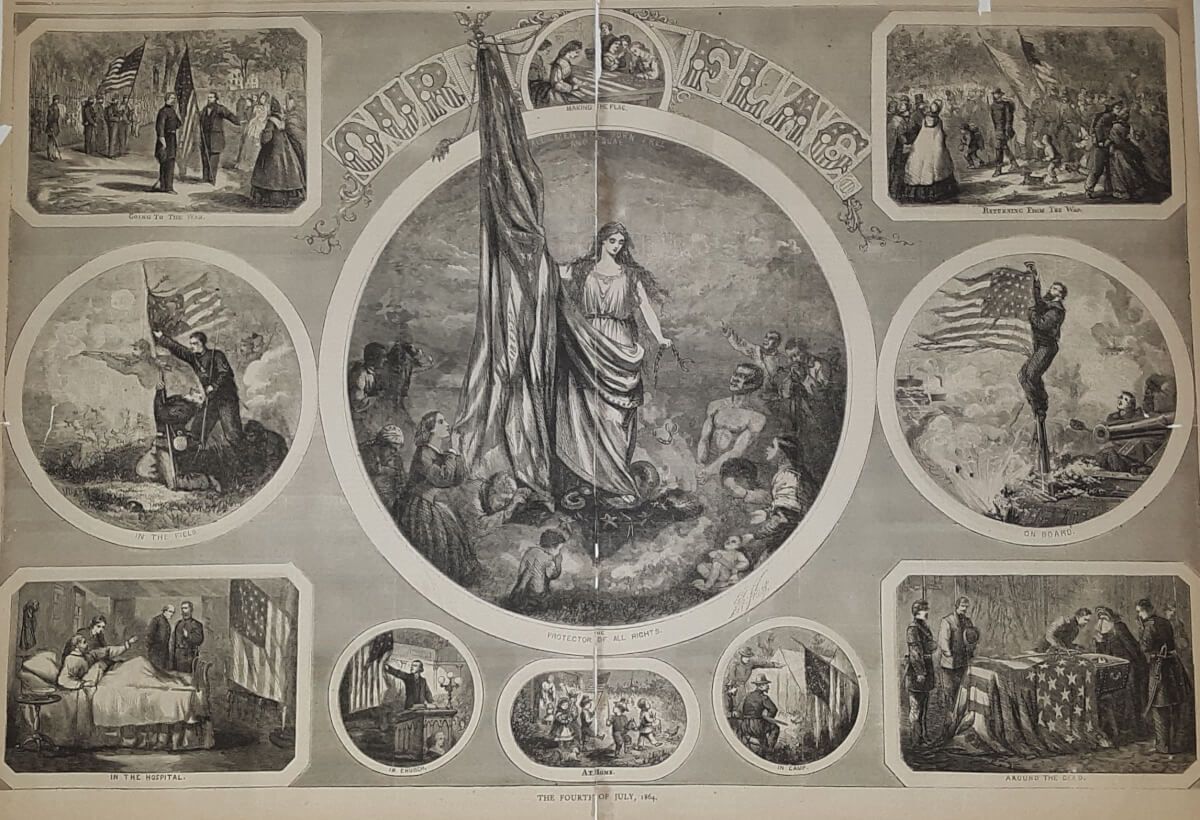

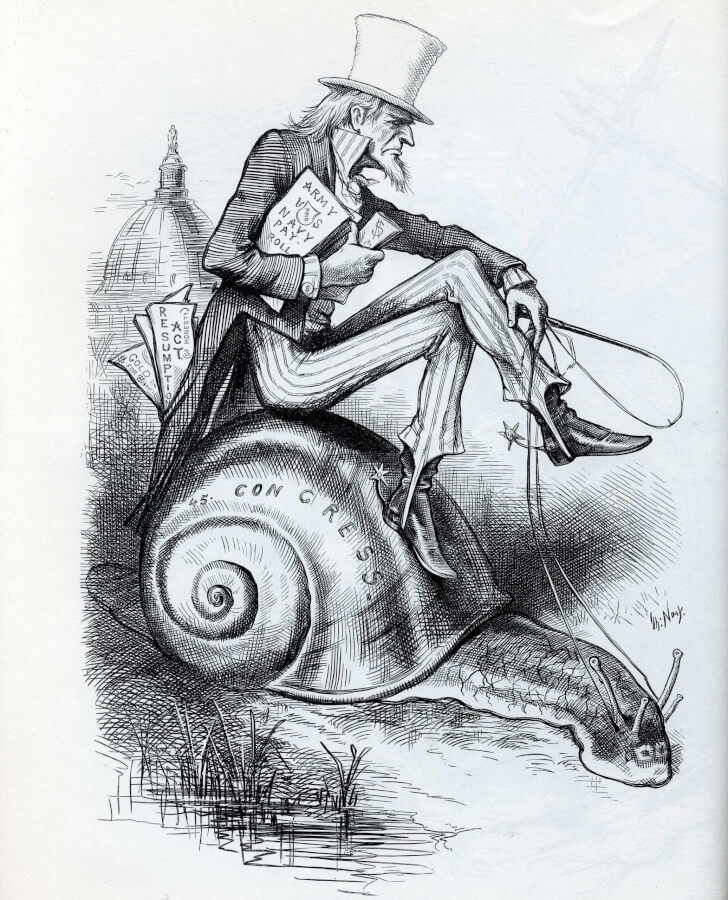

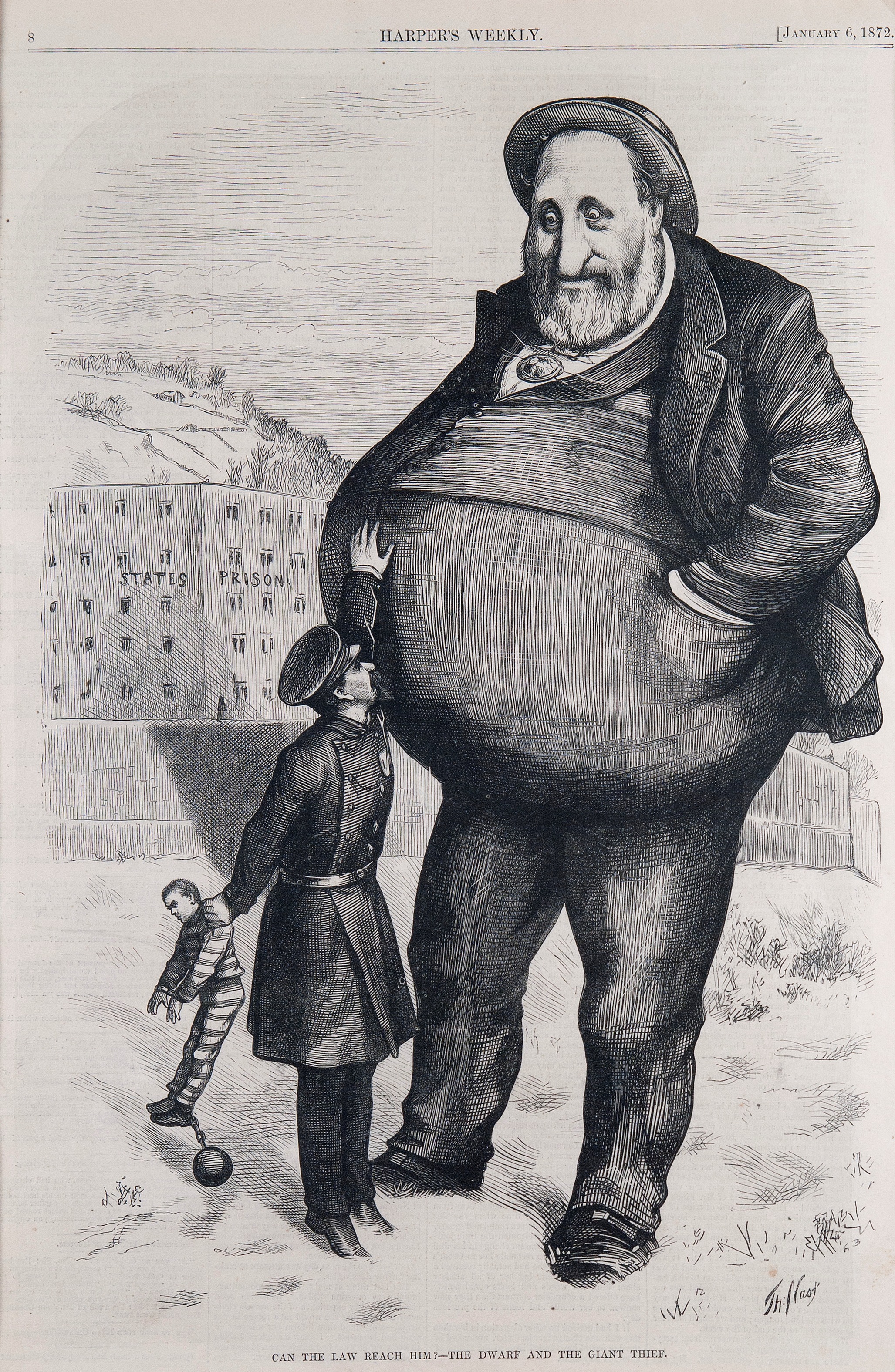

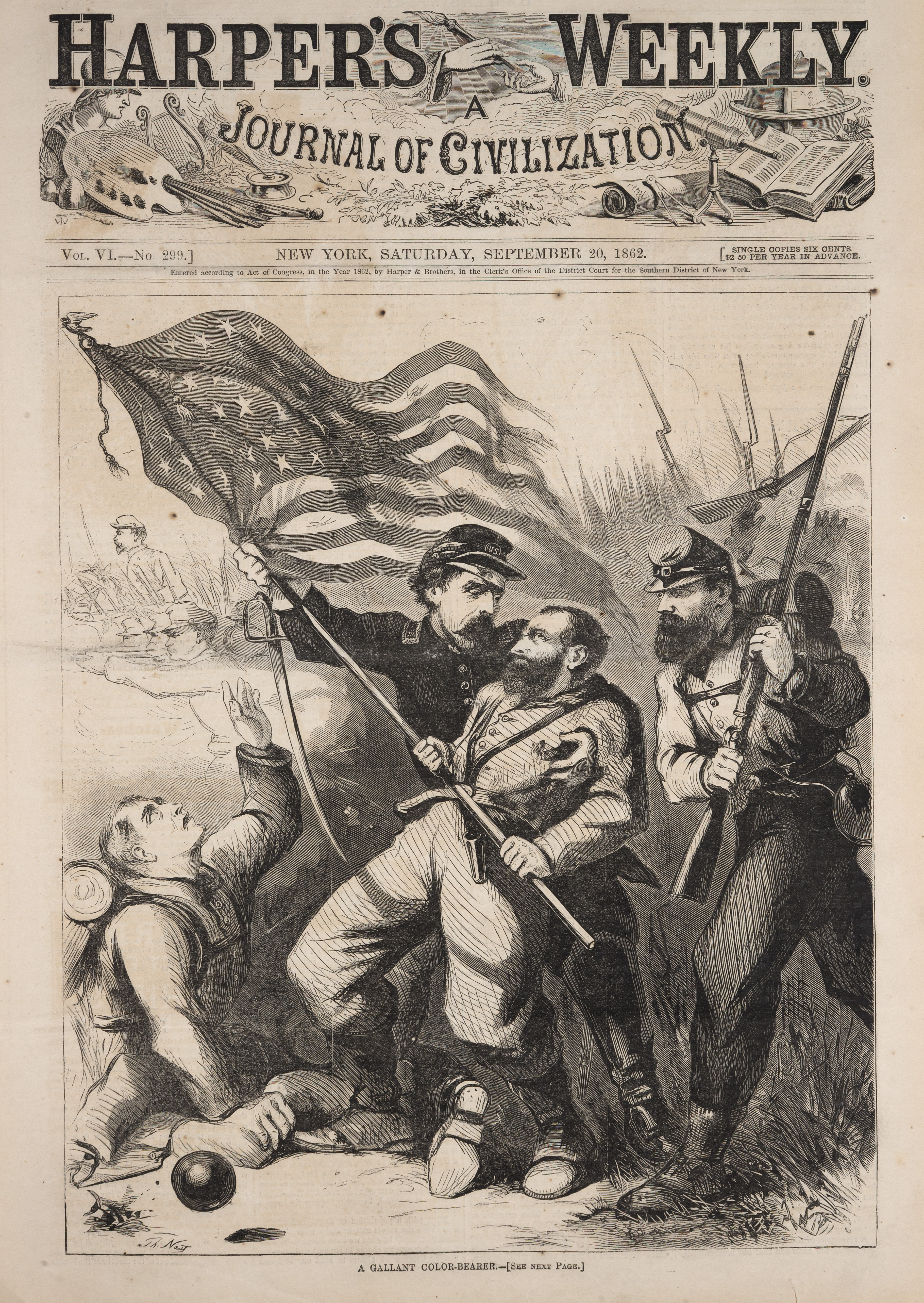

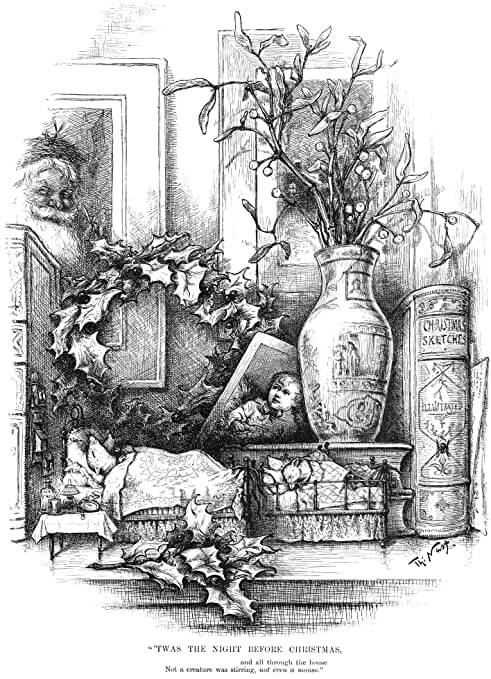

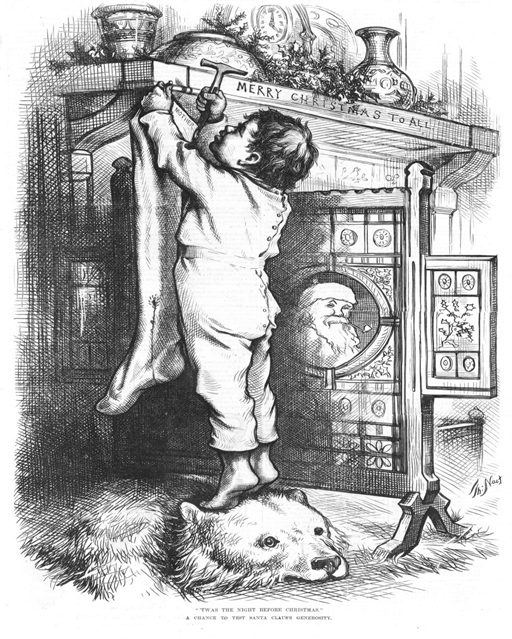

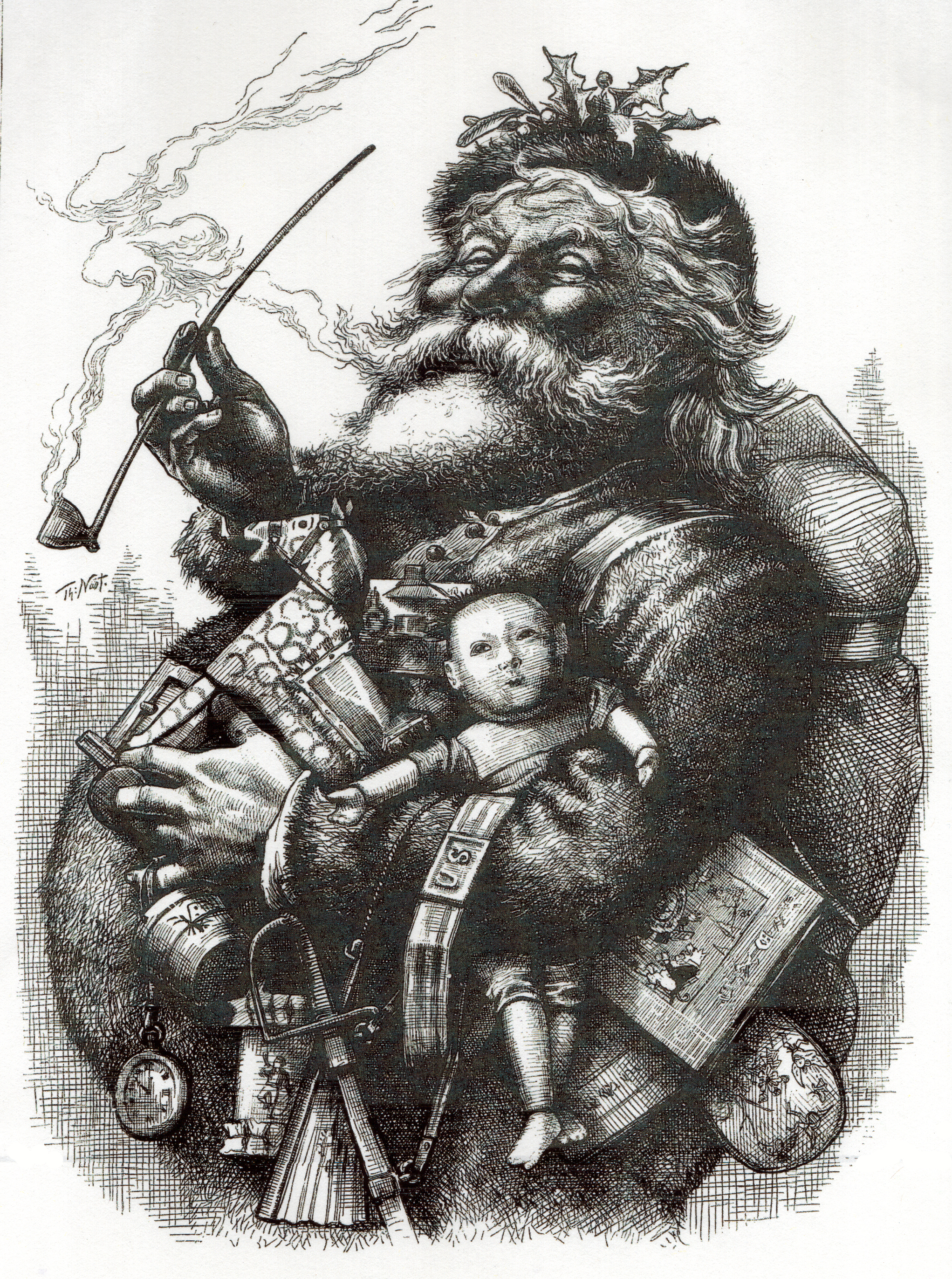

Upon his return to the United States in February 1861, Nast began to cover the American Civil War that April for New York Illustrated News. In 1862, the artist joined Harper's Weekly as its war correspondent. Just 22 years old at the time, Nast created illustrations based on reports of what was happening on the battlefield. He worked for the weekly until 1877, and again from 1895-1896. During his tenure, Nast created hundreds of cartoons including the Democratic Donkey, Republican Elephant, Uncle Sam, Columbia, Tammany Tiger and Santa Claus. Nast also created cartoons commenting on issues of the day using derogatory ethnic and racial stereotypes. Nast illustrated stereotypes of Black Americans, as well as Irish and Chinese immigrants. The artist also published Anti-Catholic cartoons attacking the Church hierarchy. At times, Nast drew derogatory caricatures in support of a person or group. In other instances, Nast used stereotypes to make a visual case against a person or group.

In 1871 Nast moved his family out of New York City to Morristown, NJ, believing it to be a safe distance from his political enemy, William "Boss" Tweed of New York. Although Nast's work for Harper's Weekly took him to New York regularly for overnight stays, Nast was an active resident of Morristown. He was an honorary member of the fire department and supported the efforts of the local lyceum and other charities. Many of Nast's drawings depict his family home since 1872, Villa Fontana, located just across the street from Macculloch Hall.

Following reversals in both his relationship with the editor of Harper's Weekly and in his personal fortune, Nast was nearly bankrupt by the turn of the nineteenth century. In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Nast a minor diplomat to Ecuador. It was the only steady paying job the artist could find. Nast traveled to Ecuador where he died of yellow fever just a few months after his arrival.

Additional Resources:

The Political Cartoonist Who Helped Lead to 'Boss' Tweed's Downfall | History.com

- A Gallant Color-Bearer

- Can the Law Reach Him? – The Dwarf and the Giant Thief

- Thomas Nast (1840-1902), “Sorrowful John and Joyful Jonathan,” 1888, Oil on canvas, TN85.01

- Self-Portrait for Christmas Card

- Thomas Nast (1840-1902), “Merry Old Santa Claus,” “Harper’s Weekly,” January 1, 1881, Engraving, TN2015.182

- Thomas Nast (1840-1902), “The Lightning Speed of Honesty,” “Harper’s Weekly,” November 24, 1877, Engraving, TN2015.179

- Stranger Things Have Happened

- Thomas Nast (1840-1902), “Grant,” “Harper’s Weekly,” June 6, 1868, Engraving, TN2004.84A-C

- Thomas Nast (1840-1902), “The Tammany Tiger Loose- What are You Going to Do About it?,” 1871, Printer’s proof, TN2004.60